Hi Franz,

Can you tell me about your first encounter with spirits? When did it become important to you?

I grew up with the smell of plum schnapps. When we had guests, they were given a shot of barrel aged plum brandy upon arrival. Nighttime meant the smell of cigars and the aroma of plum brandy. So it was just a matter of time before I could sneak a taste for myself.

Much later as an artist I realized that I was becoming more and more unhappy with my situation spending most of my time in my office buried in endless calculations and renderings on my computer screen… this as an artist! Financialization had seeped over into the art world, and my gallery was at the mercy of financial advisers, consultancy firms and the like. Having lived for a long time in New York, I had expected nothing less with Wall Street having penetrated everything. I decided to escape the art world, escape abstraction. A radical shift from that new economy to the real economy: I wanted to feel what I was doing, I wanted to smell things, I wanted to climb trees and make mash, no more being a smart ass, an artist donkey for entertaining a few billionaires. The greater experience is in seeing that the small plum you distill smells like the plum you harvested.

Did you start on a trial and error basis or did you study distillation first?

It was more learning by doing, which is more challenging and leads to more experimentation as you are uninhibited by rules. Attending a school rarely leads to change: one tends to follow a program without questioning it. On a trial error base, passion becomes the driving force in the beginning, all your senses are challenged. Doing and managing the new is mainly in the focus and not so much economic efficiency.

Where did you learn about distilling?

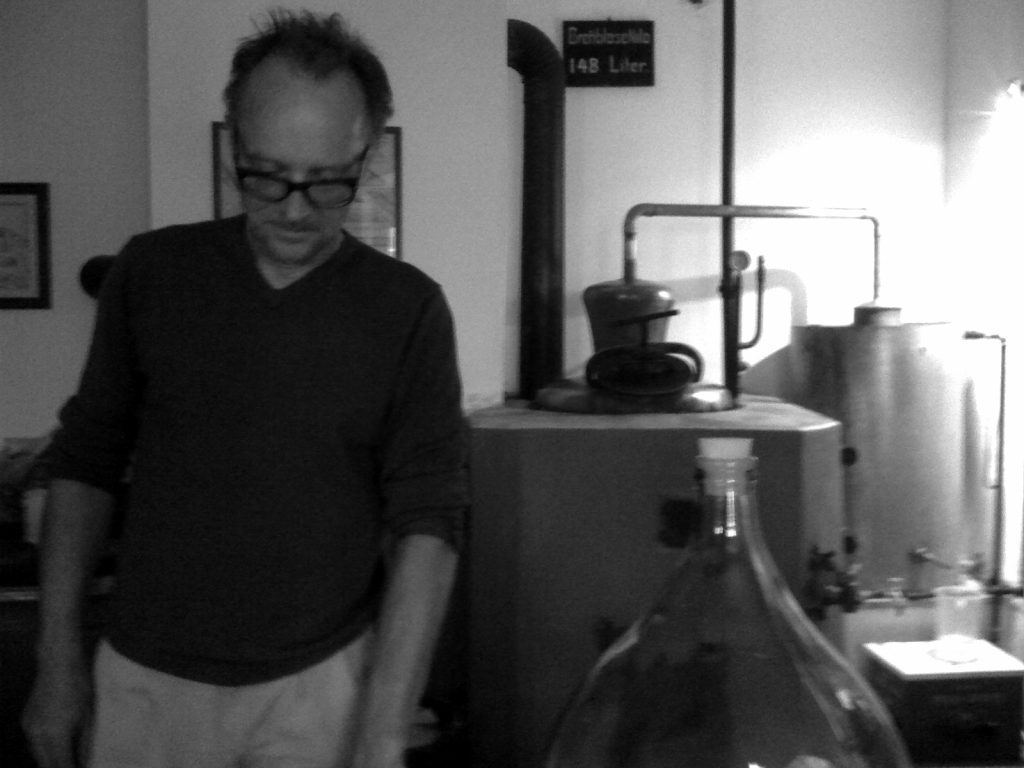

Our distillery is traditionally very small and was used for private consumption exclusively up until recently. Fifty to a hundred liters of barrel aged plum brandy per year yielded more than enough supply to keep up with the demands of being a good host! When I was growing up, a worker from the brewery was the one who traditionally prepared the mash and did the distilling, Mr. Rössle. He was the master for the ‘crafted’ beer and knew how to handle the completely manual still I’m using today. He insisted that I learn how to use this very old device. In the beginning he taught me only basics, how to mash plums and how to run the still. With his being extremely traditional and stubborn, it enabled me to rebel and do things a little different by starting to introduce other fruits and spirits. As the pot still is running with wood burning fire, I had to learn to chop down the wood to various sizes first in order to be able to keep control of the fire. Heat control is one of the most important things for this type of still, which you can only manage by adding or taking away oxygen or by opening or closing valves feeding cold water to the water bath enclosing the still.

Was it hard to learn? Is there something you do not like about being a distiller?

I’m still learning. All the bureaucracy involved of course is so archaic and such a pain in the neck. The paperwork is a real ball-breaker.

Is there a process or a step you find harder or less pleasant?

Even today, I deplore emptying the still after distilling and draining the mash.

What would say to someone who wants to start a career as a distiller?

Do not consider it unless you want to have a career, that will quite possibly lead to frustration and poverty. If you still want to become a distiller, then read about distilling and fermenting as much as you can, educate your nose and gum extensively, stay away from all those ‘marketing engineers’ and just enjoy what you want to do.

Would you consider you’re doing a craft spirit?

I harvest most of the fruits, sort and clean them, then I do the mash, chop the wood for the fire and distill every drop. I design the labels as well as perform and sell the product … if you want to call that craft?

How much does the expression make sense to you?

It’s never made sense. Even less so than the word ‘certified’, I guess ?

How do you cope with them using the word ‘craft’? What would be your definition?

Ultimately it’s not something that keeps me awake at night, but its stale employment today definitely is an insult to all those thousands of traditional distillers who do honest and competent work. Ultimately social media and lifestyle magazines have created that an abuse of the word.

Where are your base material and ingredients coming from?

Some fruits I cultivate myself, my apples I harvest every other year on park-like orchards surrounding a golf course just a few miles down the road from the distillery; the citrus fruits I get from friends in the next village who import their own fruits from an organic farm they run in Sicily; other fruits I buy regionally. For my dry and aged gins, I grow some fresh botanicals myself, and the more exotic ones I purchase from suppliers. I definitely do not drive around with a Landrover in India.

How would you describe your spirits? What makes them unique?

Unique in taste, free of hype, honestly and high-end produced by a one-man industry as an ongoing project. I like experiments that lead to the unexpected.

Did you know when you started that there would be so many new gins launched each year on the market? how do you see this profusion of choices?

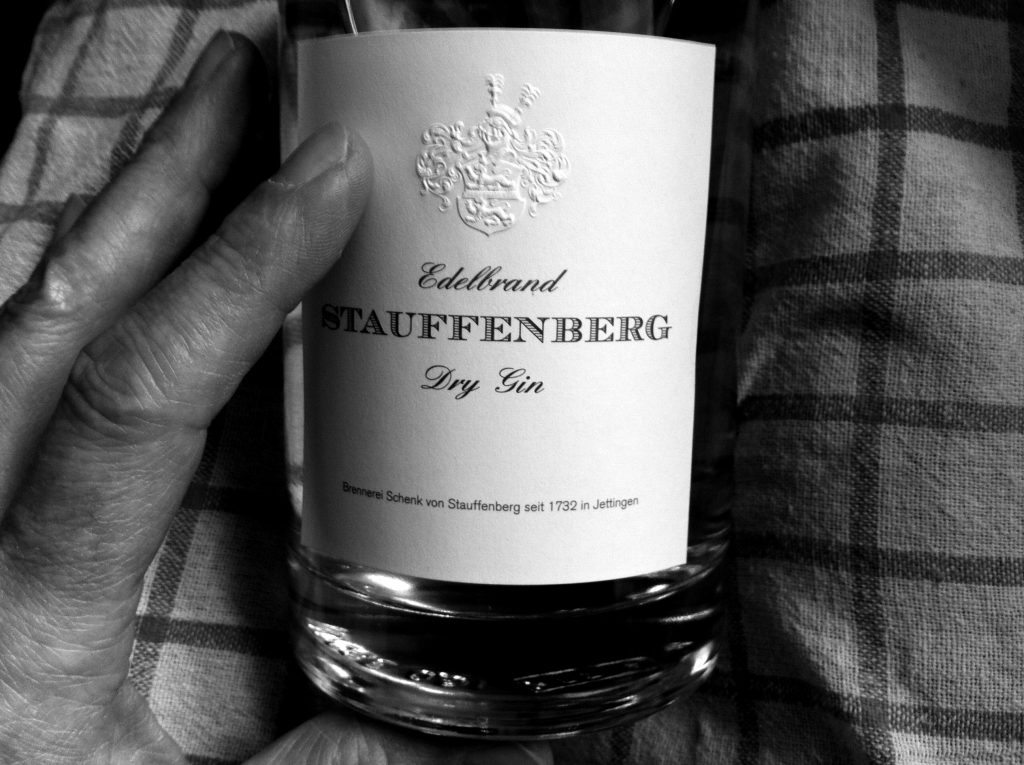

No, I had no clue. When Alexander Schröder from Galerie Neu in Berlin helped me to launch Stauffenberg in the Elgarafi popup store in 2009, we were offering fruit brandies only. Stauffenberg Gin followed in 2013 (which was launched at my wedding party at the Schinkel Pavillon): there was a hint in the air, but no, we were pretty much unaware of the tsunami of gins that were about to hit. But I have no problem with variety.

Do you know who are your clients?

Not all of them, but as I perform my products personally on many occasions, I have a lot of direct contact to my clients.

Do you think that making high-quality spirits is enough to exist in the spirits industry these days?

I believe in the niche of high quality products and I believe that in the future the market will rather expand into that direction, whereas the faceless brands and industrially produced spirits market will eventually shrink. The era of the monoliths is coming to an end, one hopes.

How do you see the major trend towards less alcohol or no alcohol in spirits?

Yeah, that will be definitely an ongoing trend and even more so, as on top of it is pretty healthy, but less fun. New to the trend is that clients are willing to consume higher quality spirits at home, less is more. Non-alcoholic spirits should be called teas or fruit juices, but definitely not spirits. I have the same problem with vegan beef.

What do you think about the idea that drug legalization could be a threat to the alcohol industry?

Ridiculous. It shouldn’t be considered a threat at all; alcohol and drugs share the same roots and looking at the extended history I believe rather that microdosing and alcohol enhance each other and open up possibilities. Just look at our Pyschological Operations Vodka, the brainchild of my brilliant wife, who is always in the woods looking for ways to use local fauna: in this case, Lion’s Mane mushrooms.

What are you working on these days that makes you excited?

We started a few collaborations with other producers, like the cocktails produced for Bottled Bar. We’ve also started introducing completely new species of liquors, such as our Hol Gur, a collaboration with our friend Simone Miller who produces a local elderflower syrup called Holla! With my friends from Sicily, I’m working on launching a liquor based on the Tarocco and blood oranges the organic farm produces. With the artist Martin Fengel, I ventured into a special edition label which is really quite humorous. We are now looking forward to spring here in the woods and our foraging expeditions. Also I’m really excited about working with Carsten Höller on “Brutalist” distillates for his project in Stockholm.

All pictures by Sorin Morar

Courtesy of Franz von Stauffenberg