Hi Theo,

Can you tell me about your first encounter with spirits? When it became something important for you?

Well, I was always fascinated with spirits. I was born in the Netherlands and I moved as a teenager to Austria. And of course there, I encountered Eaux-de-Vies and Fruit Brandies and I was always interested in how you can transform aroma or fruit into a clear spirit.

Did you start with trying and drinking or you were studying it?

As a consumer. My professional background was completely different. Then I got more and more interested in regional food and food traditions, I was finding old recipes to cook so it was like a whole variety of different approaches to flavors and aromas, always with this kind of interest of what kinds of traditions do exist within certain places and how you can transform that, how you can reinterpret these traditions.

It was actually a little bit the beginning of a general interest in food and beverages. (…)

Where did you learn about distilling then ?

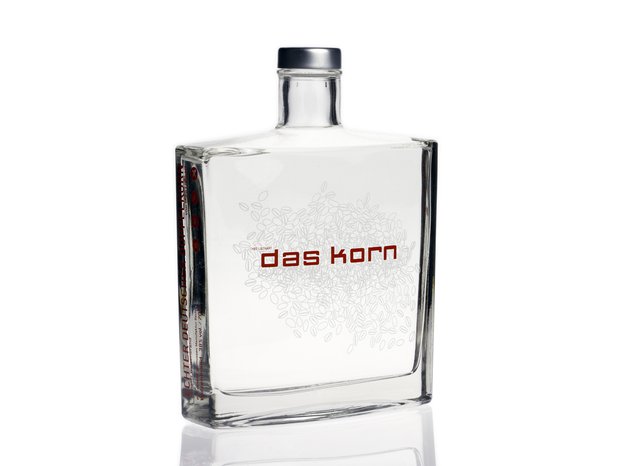

Through the (spirit) Korn. I was living here in Berlin, working as an artist and I my work was always kind of conceptual, institutional critique oriented in a way, or at least that was the background, and I wanted to do a project where the brand was an art project and the product, alcohol, could also be sold in regular shops with people not knowing that originally, it was an art project.

I was interested in Korn brand also because it has a real bad reputation here in Germany but it is also the oldest spirit, with the longest tradition here in Germany. So I was interested in this spirit category. How can you have an industrially made product sold at the low price being turned into craft spirits? (…)

At that time I didn’t even know about the expression craft spirit. But still when I was doing it, I was thinking I’m gonna do this as an art project, maybe showed it at two three shows at the gallery, and then continue doing something else. The idea was to create this kind of company as an artwork and sell it through the gallery. I did Korn in 2008 for a show at the Thomas Schülte Gallery here in Berlin, I did another one at his gallery, and then I showed part of the work at the Armory show in NYC. But at the same time I got a lot of feedback from the bar world, from the bar scene and they were enthusiastic about what I was doing, and the more I got involved, the more I produce myself, and I was producing in a small distillery in Brandenburg and this older master distiller told me how to do it, and we selected the ingredients, etc.

How did you like it? What did you like the most? What did you find the most magical?

And I liked it a lot! The very magical thing for me is of course that you have this mash, which is actually not a very nice looking, and not very nice smelling product and which turns into this liquid with incredible flavours and aromas. It is almost like a magical trick turning something kind of ugly and bad smelling into something beautiful, fresh, transparent.

And then also the variety of the process, what you can do, how you can improved taste…

Was it hard to learn?

I was just doing Korn which is, compared to fruit brandies, a more technical and easier, but still, we did a lot of testing starting with different products, using different grains. That was also very interesting; you can really go into the ingredients and have different approaches. With fruit brandies, it is different. You can tell if the fruit is ripe, you can tell there are the aromas. When you have the best quality fruit and you do everything else right, you will end up with a great product.

But Korn was or is a different type of challenge ?

Of course! You can’t just chew on a grain to say this is super ripe. So you have to you quite a lot of testing and this is what is interesting.

Is there something you also not like in the fact being a distiller? Is there a process or a step you find harder or less pleasant?

Well, I mean the hard part if you are a producer is always the distribution, which of course became much easier because when I started in 2008, nobody was interested in Korn brand because of the reputation, and secondly there were hardly any German producers around producing quality products. So yes I have to say with Monkey 47 and this German gin high which then followed, things got a lot easier and now it’s like, I don’t have to explain you can have a great German spirits. When I started in 2008 I had to say “it is a German spirit but it is good”

What would say to someone who want to start a career as a distiller?

It depends very much. I know a couple of young people who started in a very traditional way like doing an apprenticeship as a distiller. And I think if you do that this traditional handcraft education then you can basically pick a job where you want. The industry is in need of good distillers. It depends if you want to start your own distillery, this is something you should try but you have to come up with good idea and good product, it is not an easy market. Because wine is something people can drink everyday, spirits is special. People don’t buy expensive bottle often. So you need high quality.

Do you think that high quality is enough to exist in the spirits industry, even though there is a major trend towards less alcohol or no alcohol in spirits at all? What or how do you think spirits producers should react to this trend?

Well, I think there is one trend that helps producers like me a lot, this is that people are drinking less but drink better. They drink less alcohol but they are more aware of what kind of alcohol they drink. It’s good for premium products and also something hard for the German market because all those mid-size distilleries were producing for decades as cheap as possible, trying to sell as cheap as possible. They have a hard time to re invent themselves, but for premium products it is not a bad time. (…)

So you do not feel more competition?

No.

And yes.

People are living much healthier now, but there is still room for quality products. So I think this is a good thing for good products.

That makes me think again as I mentioned the less alcohol or no alcohol trends, that makes me think about the trend that consider new drug legalization in different countries as being a threat for the alcohol industry. What do you think about it ?

I mean statistics say that people are drinking less for sure. But they also say that people spend more money on alcohol. So if you have invested in quality… you’re in good shape.

And with your Kollektiv Freimeister, this is the idea right, to invest into quality right? But is craft spirits always of good quality ?

I have to tell you why I’m asking this this way.

What interested me when I discovered your collective is one sentence in your statement actually: I liked that you remind people how the market is biased, behind a myriad of alcohol brands, there are actually very few corporations, and they hide the smaller producers. I liked that you reminded your audience about it because big brands like Diageo or PR they also do premium craft spirits but they are far from small-scale / hand-made!

So you, as a collective, how do you cope with them using the word craft? Why do you keep using the word?

The term craft we defined it quite precisely for our festival: no pesticide, hand crafted, not owned by big corporations. (…)

This is something you see very much. In the biomarkets even. A lot of beer big brand are trying to fake craft. But it does not work.

In the end people are smart enough to tell the difference. I don’t worry too much.

It is difficult, of course. Every trend is very fast adopted by big companies (…) this big corporation which are trying to profit of certain trends but it is really hard for them to give authenticity.

Is it not a problem? There is no perversion of craft?

I guess we will see how the term craft will develop. We use it for the festival but I do not use it for Freimeister Kollektiv for example. For the festival we use it to make it easier to understand for the people who are not so much into the spirits world. But at the same time with experts, I would not use it so much.

What would you use?

It is really hard. In Germany for instance, we see it at the festival very much, which is also something I saw working with small distilleries. You have some kind of trendy craft producers, even those who are sitting in their advertising agency and have great visual concept for a new gin brand but who have no clue about distilling and basically buy some mediocre gin and bottled it in good looking bottles, and they call it craft. At the same time in Germany, around here, you have thousand of small distilleries, not all of them are producing great products but some do, and this, since several generations. You have a tradition, which was just not so present in the medias for a couple of years, but this is interesting because we do find this knowledge, this old knowledge about spirits production, here. (…)

So in your definition of craft, it seems it has more to do with a notion of scale? Does that mean that if you want to do craft, you have to limit yourself?

That’s always a problem but there are simple, physical limits to producing high quality spirits. It’s different if you heat up a still of 100 or 150 liters for a fruit brandy as if you scale it to 2000 liters. The whole process of the mash will not be the same, You would not be able to get the same quality out of it. That was the idea with the collective, instead of being able to scale to a certain industrial level why not creating an umbrella brand for small producers and offering bigger varieties of products instead of having one or two products and trying to scale it up.

Don’t you think it can become frustrating tolimit one’s ambitions, in terms of making a product accessible to a greater number of people?

Yes. You have to accept to limit your production. In Germany you have this limitation, the law is changing now, but most of the small fruit brandy producers until now, cannot produce mot than 300 liters of pure alcohol. The law is changing a bit but no one will be able to produce unlimited amounts.

So anyhow this legal situation is like a good way to define or preserve what craft is?

It depends also of the kind of product you are producing. It you produce, if you distill grain spirits like whisky producers, the whole distilling process is not limited to a small pot still, you see it with Scottish producers, they do have bigger pot stills than fruit brandy producers, and it is unlimited.

Fruit brandy it is limited by the quality of the ingredients you need.

We are always questioning the term craft and where does it make sense and where it is just pure nostalgia, a sentimental idea of people living in the city, who think that everything small, or everything which as a long tradition is better than before. Which is not true. I thin the spirits are better now.

If I talk to fruit brandy producers, and they tell me how their parents worked, (…) they still see themselves as a new generation because they do things differently, they focus more on quality, they have a completely different approach to the way they prepare the fruits, how they separate the tails and heart of the run, etc. Not everything that is traditional is better, because this is traditional.

Tell me more about how you work with the distillers of the collective. Do the distillers have their own brand, still even though being part of the collective for example?

Yes they do.

We don’t want the farmers to be dependent of our brand and very often locally they are very well known, they have their own customers, this is a way to first of all give them an opportunity to experiment things always approached them with the question what would you like to do? Or what you haven’t done yet? You know sometime they are limited, limited by the customers they are serving to, all different reasons, then and with the collective they have the possibility to do something without economic risks. (…)

You have few women in the collective, you told me it is gonna change, but more generally how do you see the situation in the industry ? Don’t you think it has already started to change?

I don’t know but I know that women have good sensory abilities and that’s the most important thing. Everything else you can learn but the palate, the nose, no. To be honest I have the feeling that a lot of distillers who do their product, in the end when it comes to really take a decision, where to bottle it, etc , very often their wifes are incredibly important point of the production process. I hope this is gonna change, I hope the daughters will be in the front to represent the company. I hope this is changing. That would be very positive for the spirits scene.

May I ask again about the collective, how does it work, does the company belong to every of the participants?

We started off as a company and work with the distillers and we took over the whole financial risks, we bought the alcohol from the distillers, but now that we are on the market they gonna be a share in the company that belongs to everyone, all the distillers, and through an elaborate system is being organized so that this share is divided among the distillers, according to how much you participate. First it is very important that everyone participating in the collective has the feeling that they own a share.

Does this exist in other countries?

Not this way. Of course you have Genossenschaft/Cooperatives in the wine world but generally it is also a bit different, they just deliver the grapes.

We are very much focused on the identity of the producers. But we do look a lot at wine cooperatives as an example how it legally works. It is not easy to set up a company where everyone has a certain part. Still it is a flexible company. Everybody feels their share is equal to their participations and commitment.(…)

Do some of you produce in Berlin? I’m asking this because it seems to have a movement of distilleries coming back into the cities, like in Brooklyn, London, Paris cities that are over populated whereas Berlin still have a lot of room and vacant places. So I had the impression that it could become the city where distillation can happen. What do you think about it? Is this a trend? What about Berlin?

This is a good question because for a long time it was only allowed to distill in the cities or aristocrats on their lands. Specially in this region it wasn’t allowed for small farmers to distill. Old German distilleries have actually their backgrounds in smaller cities. And now distilleries are coming back to the cities. For example in the festival there is one in Helsinki, they started the first distillery in Helsinki, the first since 150 years.

Myself I am consulting, I worked as project managers for setting up MAMPE distillery in Berlin whose main products were still produced by external producers but they wanted a more craft approach to some of their products. Till the 70s that was still produced in Berlin but then they sold the brand and it wasn’t produced here in Berlin anymore. And now a couple of years ago, somebody bought the brand and wanted to bring it back in Berlin but still with the actual products produced at external producers. Now they asked me to help them setting up their own distillery here in Berlin and it is now finished already.

But in Germany you have Distillerie and Brennerei. Brennerei is also a distillery were actual alcohol is produced. There is a mash and then the fruits, the distilling process and the alcohol is produced. Whereas a Distillerie is a place where also there is a still but they work with neutral alcohol, which is then turned into something else, like typical gin for example.

In Berlin you have the Preussiche Spirituosen Manufaktur with a long tradition here but but this is a Distillerie not a Brennerei, they don’t produce their own alcohol. They create Liqueurs, Gin, but all start with neutral alcohol which is produced somewhere else.

And there is one guy in Wedding, and he is actually a Brewer and he is actually really distilling, in the way that he has his mash that he is turning into high volume spirits and it is also that now at the end of the year there is a big change in law that will make it easier to set up Distilleries. It will be easier to create a Brennerei. Next year if you can access to a orchard you can apply to a Brennerei status which you couldn’t apply before in the former east German states. When the wall came down no one had those rights in East Germany. And it is also a big difference in financing, the Distilleries (Verschlussbrennerei) are at least 5 or 6 times more expensive to set up. that a Brennerei (Abfindungsbrennerei) (…) so it will give more dynamic to the market, it will be very interesting years to come for Berlin.

Speaking of which, you may be interested to know that we will, as the Freimeisterkollektiv soon start a Distiller-in-Residence program.

Then I guess we will meet soon again to discuss this new endeavour !